Some central banks in Europe have started weighing contingency plans to prepare for the possibility that countries leave the euro zone or the currency union breaks apart entirely, according to people familiar with the matter.

The first signs are surfacing that central banks are thinking about how to resuscitate currencies based on bank notes that haven't been printed since the first euros went into circulation in January 2002.

At least one—the Central Bank of Ireland—is evaluating whether it needs to secure additional access to printing presses in case it has to churn out new bank notes to support a reborn national currency, according to people familiar with the matter.

Outside the 17-country euro zone, numerous European central banks are eyeing defensive measures to protect against the possible fallout if the euro zone were to unravel, other people said. Several, including Switzerland, are considering possible replacements for the euro as the external reference point, or peg, they use to try to keep their currencies' values stable.

The central banks' planning is preliminary, according to the people familiar with the matter. It doesn't represent an expectation that the euro zone is headed for dissolution.

But the fact central bankers are even studying the possibility, which until this fall was considered unthinkable, underscores how swiftly conditions have deteriorated. Policy makers, central bankers and investors around the world have pinned their hopes on this week's Brussels summit to forge a long-awaited solution to the Continent's two-year financial crisis, which was ignited by doubts over countries' abilities to pay their debts.

The stakes are high. A failure of Europe's leaders to defuse the crisis would fuel already growing doubts about the viability of the euro zone. Many policy makers, bankers and other experts fear the monetary union's unraveling would not only reverse a decade of economic integration but also would trigger financial chaos.

J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. put out a report Wednesday that advised investors and companies to hedge against a collapse of the euro zone—though the bank said the likelihood of that happening was just 20%. It said many corporate clients were buying currency derivatives to place bets against the euro.

Before the formal launch of the euro in January 2002, an army of planners spent years choreographing the logistics of the currency's debut, including the minting of billions of bank notes and coins and the distribution of the new currency to banks and businesses across the Continent. Disassembling the bloc would be messy at best. Among the many challenges, loans and deposits currently denominated in euros would have to be switched to new currencies. And individual countries would need to decide whether to dust off their old currencies and, if so, how to quickly produce large quantities of paper money.

In Montenegro, which used Germany's Deutsche mark as legal tender before it adopted the euro in 2002, central bank officials are weighing their options for life after the euro. The Balkan country would have "a wide range of possibilities, from using another foreign currency to the introduction of a domestic currency," said Nikola Fabris, chief economist at Montenegro's central bank. One problem with the latter option: Montenegro doesn't have the capacity to print its own money, he said.

Most euro-zone central banks maintain at least limited capacities to print bank notes. While the European Central Bank is responsible for determining the euro zone's supply of bank notes, it doesn't actually print them. The ECB outsources the work to central banks of euro-zone countries. Each year, groups of countries are assigned the task of printing millions of bank notes in specific denominations.

The countries have different arrangements for printing their shares of the notes. Some, like Greece and Ireland, own their printing presses. Others outsource to private companies.

The assignments vary from year to year. Last year, Ireland printed 127.5 million €10 notes, and nothing else, according to its annual report. This year, it was among 11 countries assigned to print a total of 1.71 billion €5 notes.

In recent weeks, officials at Ireland's central bank have held preliminary discussions about whether they might need to acquire additional printing capacity in case the euro zone ruptures or Ireland exits in order to return to its prior currency, the Irish pound, according to people familiar with the matter. Officials have discussed reactivating old printers or enlisting a private company, the people said. "All kinds of things are being looked at that weren't being looked at two months ago," according to a person at one meeting. A spokeswoman for the Irish Central Bank declined to comment.

In Greece, widely regarded as the country most likely to leave the euro zone because of its fiscal problems, the central bank has a bank-note printing facility called IETA. Built in 1941, the Attica plant today is outfitted with "state-of-the-art machinery," according to the Bank of Greece's website. But IETA's printing in recent years has been limited. It has been one of five or six countries responsible for printing batches of €10 notes, according to the ECB.

Athens has buzzed with rumors over the past year that the Bank of Greece was secretly printing drachmas, Greece's pre-euro currency. Widely circulated joke emails featured drachma bank notes bearing the image of then-Prime Minister George Papandreou. The rumors at times have been blamed for triggering waves of withdrawals from Greek retail banks.

A Bank of Greece spokesman said the bank isn't looking for ways to boost its printing capacity. "There has been no talk regarding this issue," he said.

Some euros are currently produced outside the euro zone. In the northern England city of Gateshead, for example, a De La Rue PLC plant prints bank notes on behalf of several euro-zone countries, according to people familiar with the matter.

The Gateshead facility also serves as a backup plant for the Bank of England, which has a separate contract with De La Rue to print British pounds, according to a Bank of England spokesman.

The situation has worried some Bank of England officials, according to a person familiar with the matter. The concern is that if the euro zone unraveled, the Gateshead facility could be overwhelmed with requests from former euro-zone countries to print their national currencies, the person said.

That has prompted the Bank of England to consider steps to ensure that its ability to print British pounds isn't compromised, the person said.

The Bank of England spokesman said the bank isn't looking to "gain additional access to De La Rue's facility in Gateshead." A De La Rue spokeswoman declined to comment.

While some euro-zone countries have their own printing presses, "there might be other opportunities arising from any possible breakup of the euro as many of the smaller countries don't have state printing works," said Tim Cobbold, De La Rue's chief executive, in a statement. He noted that it usually takes about six months to develop a new currency with the necessary security features.

In Switzerland, which like the U.K. isn't part of the euro zone, the central bank has used the euro as its external reference point in its efforts to keep the Swiss franc's value stable.

Now, officials at the Swiss National Bank are considering what currency or basket of currencies would replace the euro as its reference point for the currency ceiling, according to a person familiar with the situation.

Before the advent of the euro, Germany's mark was Switzerland's main point of reference—including a period in the 1970s when the Swiss National Bank pegged the franc against the mark to rein in a surge in the Swiss currency. Today, as in the 1970s, Germany is Switzerland's largest trading partner, so a new Deutsche mark could in theory substitute for the euro, according to this person, although the bank is considering other scenarios, such as the formation of more than one currency bloc within Europe.

Central bank officials in Bosnia and Herzegovina, whose convertible mark is currently pegged to the euro, could switch to whatever hard currency emerges in the case of a breakup of the euro, a spokeswoman said. Before Bosnian officials fixed the national currency against the euro in 2002, they used the Deutsche mark as the peg.

Latvia's currency, the lat, is also pegged to the euro. The country's central bank doesn't expect the euro's demise but "could be expected" to look for a potential new peg among other European countries with "prudent fiscal policies" and with which Latvia already trades heavily, said a spokesman for Latvijas Banka.

Source: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203413304577084483874422516.html?mod=WSJAsia_hpp_LEFTTopStories

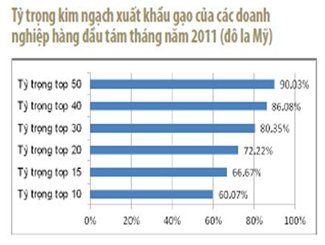

Giả sử có giới đầu tư tài chính nhảy vào thì “miếng bánh” sẽ được chia nhỏ hơn, tức tỷ trọng xuất khẩu của nhóm doanh nghiệp nói trên sẽ giảm xuống trong tổng lượng xuất khẩu. Tuy nhiên, số liệu so sánh tám tháng đầu năm 2011 và cả năm 2010 cho thấy các tỷ trọng của top 10, 15, 20... trong tổng xuất khẩu không có sự dịch chuyển nào đáng kể. Như vậy, có thể khẳng định ít nhất cho đến thời điểm hiện tại, giới đầu tư tài chính vẫn chưa thao túng được khâu xuất khẩu gạo, hoặc mức đầu tư chưa đủ lớn để xoay chuyển tình hình.

Giả sử có giới đầu tư tài chính nhảy vào thì “miếng bánh” sẽ được chia nhỏ hơn, tức tỷ trọng xuất khẩu của nhóm doanh nghiệp nói trên sẽ giảm xuống trong tổng lượng xuất khẩu. Tuy nhiên, số liệu so sánh tám tháng đầu năm 2011 và cả năm 2010 cho thấy các tỷ trọng của top 10, 15, 20... trong tổng xuất khẩu không có sự dịch chuyển nào đáng kể. Như vậy, có thể khẳng định ít nhất cho đến thời điểm hiện tại, giới đầu tư tài chính vẫn chưa thao túng được khâu xuất khẩu gạo, hoặc mức đầu tư chưa đủ lớn để xoay chuyển tình hình.

![[LOANHERD]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BM514_LOANHE_NS_20111206173002.jpg)