Workers on tap

IN THE early 20th century Henry Ford combined moving assembly lines with mass labour to make building cars much cheaper and quicker—thus turning the automobile from a rich man’s toy into transport for the masses. Today a growing group of entrepreneurs is striving to do the same to services, bringing together computer power with freelance workers to supply luxuries that were once reserved for the wealthy. Uber provides chauffeurs. Handy supplies cleaners. SpoonRocket delivers restaurant meals to your door. Instacart keeps your fridge stocked. In San Francisco a young computer programmer can already live like a princess.

Yet this on-demand economy goes much wider than the occasional luxury. Click on Medicast’s app, and a doctor will be knocking on your door within two hours. Want a lawyer or a consultant? Axiom will supply the former, Eden McCallum the latter. Other companies offer prizes to freelances to solve R&D problems or to come up with advertising ideas. And a growing number of agencies are delivering freelances of all sorts, such as Freelancer.com and Elance-oDesk, which links up 9.3m workers for hire with 3.7m companies.

The on-demand economy is small, but it is growing quickly (see article). Uber, founded in San Francisco in 2009, now operates in 53 countries, had sales exceeding $1 billion in 2014 and a valuation of $40 billion. Like the moving assembly line, the idea of connecting people with freelances to solve their problems sounds simple. But, like mass production, it has profound implications for everything from the organisation of work to the nature of the social contract in a capitalist society.

Baby, you can drive my car—and stock my fridge

Some of the forces behind the on-demand economy have been around for decades. Ever since the 1970s the economy that Henry Ford helped create, with big firms and big trade unions, has withered. Manufacturing jobs have been automated out of existence or outsourced abroad, while big companies have abandoned lifetime employment. Some 53m American workers already work as freelances.

But two powerful forces are speeding this up and pushing it into ever more parts of the economy. The first is technology. Cheap computing power means a lone thespian with an Apple Mac can create videos that rival those of Hollywood studios. Complex tasks, such as programming a computer or writing a legal brief, can now be divided into their component parts—and subcontracted to specialists around the world. The on-demand economy allows society to tap into its under-used resources: thus Uber gets people to rent their own cars, and InnoCentive lets them rent their spare brain capacity.

The other great force is changing social habits. Karl Marx said that the world would be divided into people who owned the means of production—the idle rich—and people who worked for them. In fact it is increasingly being divided between people who have money but no time and people who have time but no money. The on-demand economy provides a way for these two groups to trade with each other.

This will push service companies to follow manufacturers and focus on their core competencies. The “transaction cost” of using an outsider to fix something (as opposed to keeping that function within your company) is falling. Rather than controlling fixed resources, on-demand companies are middle-men, arranging connections and overseeing quality. They don’t employ full-time lawyers and accountants with guaranteed pay and benefits. Uber drivers get paid only when they work and are responsible for their own pensions and health care. Risks borne by companies are being pushed back on to individuals—and that has consequences for everybody.

Obamacare and Brand You

The on-demand economy is already provoking political debate, with Uber at the centre of much of it. Many cities, states and countries have banned the ride-sharing company on safety or regulatory grounds. Taxi drivers have staged protests against it. Uber drivers have gone on strike, demanding better benefits. Techno-optimists dismiss all this as teething trouble: the on-demand economy gives consumers greater choice, they argue, while letting people work whenever they want. Society gains because idle resources are put to use. Most of Uber’s cars would otherwise be parked in the garage.

The truth is more nuanced. Consumers are clear winners; so are Western workers who value flexibility over security, such as women who want to combine work with child-rearing. Taxpayers stand to gain if on-demand labour is used to improve efficiency in the provision of public services. But workers who value security over flexibility, including a lot of middle-aged lawyers, doctors and taxi drivers, feel justifiably threatened. And the on-demand economy certainly produces unfairnesses: taxpayers will also end up supporting many contract workers who have never built up pensions.

This sense of nuance should inform policymaking. Governments that outlaw on-demand firms are simply handicapping the rest of their economies. But that does not mean they should sit on their hands. The ways governments measure employment and wages will have to change. Many European tax systems treat freelances as second-class citizens, while American states have different rules for “contract workers” that could be tidied up. Too much of the welfare state is delivered through employers, especially pensions and health care: both should be tied to the individual and made portable, one area where Obamacare was a big step forward.

But even if governments adjust their policies to a more individualistic age, the on-demand economy clearly imposes more risk on individuals. People will have to master multiple skills if they are to survive in such a world—and keep those skills up to date. Professional sorts in big service firms will have to take more responsibility for educating themselves. People will also have to learn how to sell themselves, through personal networking and social media or, if they are really ambitious, turning themselves into brands. In a more fluid world, everybody will need to learn how to manage You Inc.

The future of work: There’s an app for that

HANDY is creating a big business out of small jobs. The company finds its customers self-employed home-helps available in the right place and at the right time. All the householder needs is a credit card and a phone equipped with Handy’s app, and everything from spring cleaning to flat-pack-furniture assembly gets taken care of by “service pros” who earn an average of $18 an hour. The company, which provides its service in 29 of the biggest cities in the United States, as well as Toronto, Vancouver and six British cities, now has 5,000 workers on its books; it says most choose to work between five hours and 35 hours a week, and that the 20% doing most earn $2,500 a month. The company has 200 full-time employees. Founded in 2011, it has raised $40m in venture capital.

Handy is one of a large number of startups built around systems which match jobs with independent contractors on the fly, and thus supply labour and services on demand. In San Francisco—which is, with New York, Handy’s hometown, ground zero for this on-demand economy—young professionals who work for Google and Facebook can use the apps on their phones to get their apartments cleaned by Handy or Homejoy; their groceries bought and delivered by Instacart; their clothes washed by Washio and their flowers delivered by BloomThat. Fancy Hands will provide them with personal assistants who can book trips or negotiate with the cable company. TaskRabbit will send somebody out to pick up a last-minute gift and Shyp will gift-wrap and deliver it. SpoonRocket will deliver a restaurant-quality meal to the door within ten minutes.

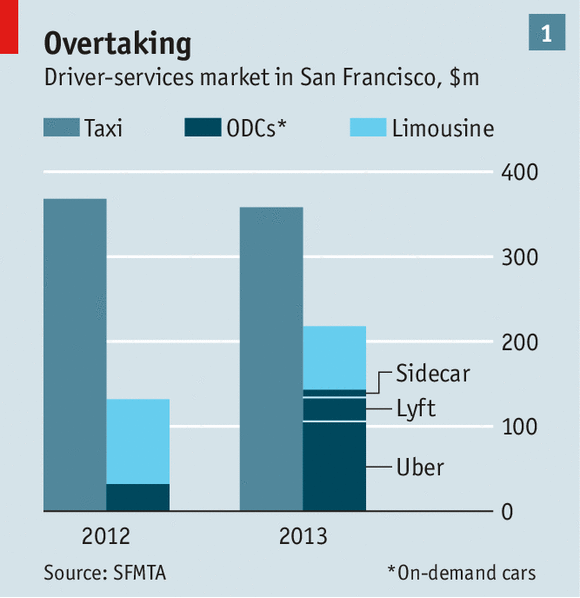

The obvious inspiration for all this is Uber, a car service which was founded in San Francisco in 2009 and which already operates in 53 countries; insiders say it will have sales of more than $1 billion in 2014. SherpaVentures, a venture-capital company, calculates that Uber and two other car services, Lyft and Sidecar, made $140m in revenues in San Francisco in 2013, half what the established taxi companies took (see chart 1), and the company shows every sign of doing the same wherever local regulators give it room. Its latest funding round valued it at $40 billion. Even in a frothy market, that is a remarkable figure.

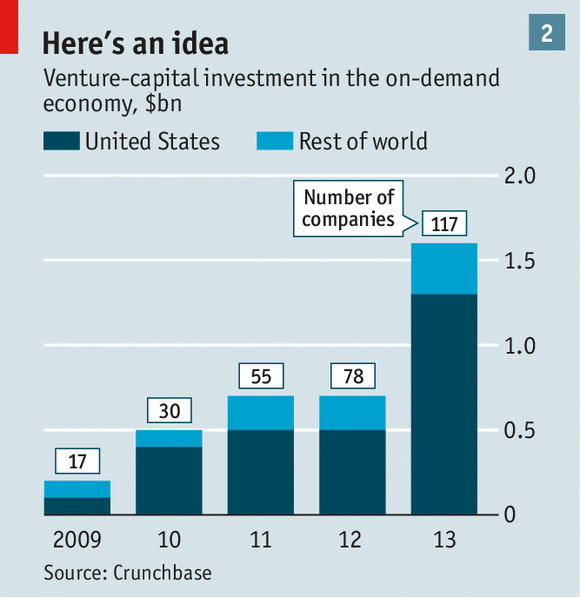

Bashing Uber has become an industry in its own right; in some circles, though, applying its business model to any other service imaginable is even more popular. There seems to be a near-endless succession of bright young people promising venture capitalists that they can be “the Uber of X”, where X is anything one of those bright young people can imagine wanting done for them (see chart 2). They have created a plethora of on-demand companies that put time-starved urban professionals in timely contact with job-starved workers, creating a sometimes distasteful caricature of technology-driven social disparity in the process; an article about the on-demand economy by Kevin Roose in New York magazine began with the revelation that the housecleaner he hired through Homejoy lived in a homeless shelter.

This boom marks a striking new stage in a deeper transformation. Using the now ubiquitous platform of the smartphone to deliver labour and services in a variety of new ways will challenge many of the fundamental assumptions of 20th-century capitalism, from the nature of the firm to the structure of careers.

The young Turks

The new opportunities that technology offers for matching jobs to workers were being exploited well before Uber. Topcoder was founded in 2001 to give programmers a venue to show off. In 2013, it was bought by Appirio, a cloud-services company, and now specialises in providing the services of freelance coders. Elance-oDesk offers 4m companies the services of 10m freelances. The model is also gaining ground in the professions. Eden McCallum, which was founded in London in 2000, can tap into a network of 500 freelance consultants in order to offer consulting services at a fraction of the cost of big consultancies like McKinsey. This allows it to provide consulting to small companies as well as to concerns like GSK, a pharma giant. Axiom employs 650 lawyers, services half the Fortune 100 companies, and enjoyed revenues of more than $100m in 2012. Medicast is applying a similar model to doctors in Miami, Los Angeles and San Diego. Patients order a doctor by touching an app (which also registers where they are). A doctor briefed on the symptoms is guaranteed to arrive within two hours; the basic cost is $200 a visit. Not least because it provides malpractice insurance, the company is particularly attractive to moonlighters who want to top up their income, younger doctors without the capital to start their own practices and older doctors who want to set their own timetables.

The Los Angeles-based Business Talent Group provides bosses on tap for companies that want to tackle a specific problem without adding another senior executive to the payroll: Fox Mobile Entertainment, an online-content provider, turned to it for a temporary creative director to produce a new line of products. Creative companies add a twist to the model: they demand ideas, rather than labour and services, and give a prize or prizes only to the ones they find interesting. Innocentive has applied the prize idea to corporate R&D; it turns companies’ research needs into specific problems and pays for satisfactory solutions to them.

A job for the afternoon

Tongal does the same thing with its network of 40,000 video-makers. In 2012 Colgate-Palmolive, a consumer-goods company, offered $17,000 to anyone who could make a 30-second advertisement for the internet. The ad was so good that the company showed it at the Super Bowl alongside blockbuster ads that cost hundreds of times more. Members of the Quirky network post their product ideas on the company’s website. Other members vote on the attractiveness of each idea and come up with ways of turning it into reality. Since its birth in 2009 the company has acquired over a million members and brought 400 products to the shops.

Perhaps the most striking of all the on-demand services is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, which allows customers to post any “human intelligence task”, from flagging objectionable content on websites to composing text messages; workers on the site choose what to do according to task and price. The set-up uses to the full most of the capabilities and advantages that make on-demand business models attractive: no need for offices; no full-time contract employees; the clever use of computers to repackage one set of people’s needs into another set of people’s tasks; and an ability to access spare time and spare cognitive capacity all across the world.

The idea that having a good job means being an employee of a particular company is a legacy of a period that stretched from about 1880 to 1980. The huge companies created by the Industrial Revolution brought armies of workers together, often under a single roof. In its early stages this was a step down for many independent artisans who could no longer compete with machine-made goods; it was a step up for day-labourers who had survived by selling their labour to gang masters.

These companies introduced a new stability into work, a structure which differentiated jobs from one another more clearly than before, thus providing defined roles and new paths of career progress. Many of the jobs were unionised, and the unions fought to improve their members’ benefits. Governments eventually built stable employment along these lines into the heart of welfare legislation. A huge class of white-collar workers enjoyed secure jobs administering the new economy.

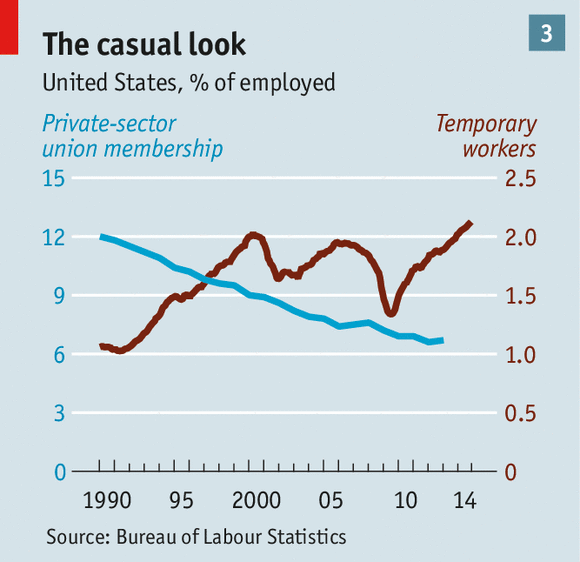

For a while after the second world war everybody seemed to benefit from this model: workers got security, benefits and steady wage rises; companies got a stable workforce in which they could invest with a fair expectation of returns. But the model started to get into trouble in the 1970s, thanks first to deteriorating industrial relations and then to globalisation and computerisation. Trade unions have lost power in the private sector, particularly in America and Britain, where legislation has reduced their ability to take action (see chart 3). Companies kept stricter control of their labour costs, increasingly contracting out production in industrial businesses and re-engineering middle-management. Computerisation and improved communications then sped the process up, making it easier for companies to export jobs abroad, to reshape them so that they could be done by less skilled contract workers, or to eliminate them entirely.

This has all resulted in a more rootless and flexible labour force. Pensioners and parents wanting or needing to spend more time on child care swell the ranks of students and the straightforwardly unemployed. A recent study by the Freelancers Union, a pressure group for freelance workers, suggests that one in three members of the American workforce (and a higher proportion of younger people) do some freelance work.

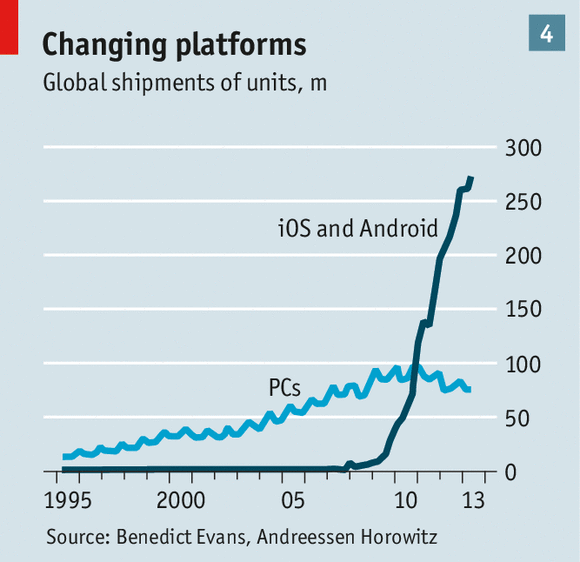

The on-demand economy is the result of pairing that workforce with the smartphone, which now provides far more computing power than the desktop computers which reshaped companies in the 1990s, and to far more people (see chart 4 on next page). According to Benedict Evans of Andreessen Horowitz, the new iPhones sold over the weekend of their release in September 2014 contained 25 times more computing power than the whole world had at its disposal in 1995. Connected to each other and to yet more data and processing power in the cloud, these devices are letting people design or find ad hoc answers to all sorts of business problems previously solved by the structure of the firm.

Coase and effect

The way economists understand firms is largely based on an insight of the late Ronald Coase. Firms make sense when the cost of organising things internally through hierarchies is less than the cost of buying things from the market; they are a way of dealing with the high transaction costs faced when you need to do something moderately complicated. Now that most people carry computers in their pockets which can keep them connected with each other, know where they are, understand their social network and so on, the transaction costs involved in finding people to do things can be pushed a long way down.

This has a range of knock-on consequences, all of which are becoming key features of the on-demand economy. One is further division of labour. Thomas Malone, of the MIT Sloan School of Management, argues that computer technology is producing an age of hyper-specialisation, as the process that Adam Smith observed in a pin factory in the 1760s is applied to more sophisticated jobs.

Another is the ability to tap underused capacity. This applies not just to people’s time, but also to their assets: to drive for Lyft or Uber, you do need a car. The on-demand economy is in many ways a continuation of what has been called the “sharing economy” exemplified by Airbnb, a company which turns apartments into guesthouses and their owners into hoteliers. For people with few assets, though, on-demand labour markets matter more.

And new areas are being opened to economies of scale. SpoonRocket prepares its food in two central kitchens in San Francisco and Berkeley. It delivers food quickly because it keeps a fleet of cars, equipped with thermal bags to keep the food warm, roaming the streets of San Francisco. “We’re like a gigantic cafeteria serving all of San Francisco,” says Anson Tsui, one of the company’s founders.

Scheduling success

The aim of the on-demand companies is to exploit low transaction costs in a number of ways. One key is providing the sort of trust that encourages people to take a punt on the unfamiliar. Customers worry about the quality of their temporary employees: nobody wants to give the key to their apartment to a potential burglar, or their health details to a dud doctor. Potential freelances, for their part, do not want to have to deal with deadbeats: about 40% of freelances are currently paid late.

On-demand companies like Handy provide customers with a guarantee that workers are competent and honest; Oisin Hanrahan, the company’s founder, says that more than 400,000 people have applied to join the platform, but only 3% of applicants get through its selection and vetting process. The workers, for their part, can hope for a steady flow of jobs and prompt payment with minimal fuss. Handy’s computer system also tries to schedule each worker’s jobs in such a way as to minimise travel time.

Despite these capabilities, Handy is not necessarily looking at huge success, any more than the other Ubers-of-X are. There are three reasons for scepticism about their chances.

The first is that on-demand companies trying to keep the costs to their clients as low as possible have difficulties training, managing and motivating workers. MyClean, a cleaning service based in New York City, tried using purely contract workers, but discovered that it got better customer ratings if it used permanent staff. The company thinks that better services justify higher labour costs. Uber drivers complain that the company pays them like contract workers while seeking to manage them like regular employees: they are told to take regular rather than premium fares, but are not reimbursed for their fuel. America’s gathering economic recovery may make it harder for companies to attract casual labour as easily as they have done in the past few years.

The second problem is that on-demand companies seem likely to be plagued by regulatory and political problems if they get large enough for people to notice them. American on-demand companies are terrified that they will be stuck with retrospective labour bills if the courts force them to reclassify their workers as regular employees rather than contract workers (a classification which is not always consistent from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, raising the level of anxiety). Handy at one point included a clause in its contracts imposing any such retrospective costs on its clients, though it has now withdrawn it.

Faced by the threat of Uber, established taxi companies around the world have organised strikes, filed lawsuits and leant on regulators. In the Netherlands Uber has been banned; South Korea is treating it as an illegal taxi service. In Germany anti-Uber feeling has nurtured a broader criticism of “Plattform-Kapitalismus”; its perceived readiness to reduce all aspects of people’s lives, from spare rooms to spare time, to assets to be auctioned off is seen as deeply dehumanising. But such protests often act as advertising for the services they are aimed against. And a recent study revealed that American politicos spend more on Uber than on regular taxis when campaigning, a strong indication that the road ahead is likely to remain clear.

The third issue is size. The on-demand model obviously has network effects: the home-help company with the most help on the books has the best chance of providing a handyman at 10:30 sharp. Yet scaling up may be difficult when barriers to entry are low and bonds of loyalty are non-existent. It will be hard to get workers to be loyal to just one middleman. A number of Uber drivers also work for Lyft.

In many service industries it is hard to see obvious economies of scale on a national or global level. Being the best dry-cleaning service in Cleveland does not necessarily offer a killer edge in Cologne. And taste can be fickle, especially with companies that often look like positional goods that trade, at least in part, on the cachet that they confer to their consumers. Many of the people who currently regard SpoonRocket as cool may drop it if it becomes a national brand. On-demand companies may find themselves stuck in a world of low margins, high promotional costs and labour churn as they struggle to attain the sort of market dominance that locks in their network advantages. Alfred, a subscription service, is already aggregating the work of specific on-demand companies such as Instacart and Handy to offer its Boston members a one-stop shop; such aggregation could drive down prices for the basic on-demand providers yet further.

Everyone a corporation

Even if the eventual on-demand victors do carve out profitable domestic-service businesses, many observers doubt that their model is more broadly applicable. Some critics argue that on-demand companies like BloomThat and Handy may be capable of delivering flowers or cleaning houses, but when it comes to companies in the main flow of the knowledge economy they are destined to remain marginal. This objection, though, is not very convincing. The sort of people currently using Uber are subject to the same forces as the people who drive them from place to place.

The knowledge economy is subject to the same forces as the industrial and service economies: routinisation, division of labour and contracting out. A striking proportion of professional knowledge can be turned into routine action, and the division of labour can bring big efficiencies to the knowledge economy. Topcoder can undercut its rivals by 75% by chopping projects into bite-sized chunks and offering them to its 300,000 freelance developers in 200 countries as a series of competitive challenges. Knowledge-intensive companies are already contracting out more work to the market, partly to save costs and partly to free up their cleverest workers to focus on the things that add the most value. In 2008 Pfizer, a pharma company, undertook a huge self-examination under the heading PfizerWorks. It realised that its most highly skilled workers were spending 20% to 40% of their time on routine work—entering data, producing PowerPoint slides, doing research on the web. The company now contracts out much of this work.

Thus more and more of the routine parts of knowledge work can be parcelled out to individuals, just as they were previously parcelled out to companies. This could be bad news for the business models of professional-service companies which use juniors to do fairly routine work—thus providing the firm with income and the juniors with training—while the partners do the more sophisticated stuff. As on-demand solutions and automation prove applicable to more and more routine work, that model becomes hard to sustain. InCloudCounsel undercuts big law firms by as much as 80% thanks to an army of freelances that processes legal documents (such as licences, accreditation and non-disclosure agreements) for a flat fee.

The key role that cutting things up into routines plays in both spheres suggests that the interaction between the on-demand economy and automation will be a complex one. Gobbetising jobs with the aim of parcelling them out to people who don’t see or need to see the big picture is not that different from gobbetising them in a way that allows automation. Often the first activity may prove a prelude to the second; it is easy to see Uber as a forerunner to an eventual system that has no drivers at all. In other cases, though, the cost-efficiency of contracting out may reduce the incentives to automate.

What sort of world will this on-demand model create? Pessimists worry that everyone will be reduced to the status of 19th-century dockers crowded on the quayside at dawn waiting to be hired by a contractor. Boosters maintain that it will usher in a world where everybody can control their own lives, doing the work they want when they want it. Both camps need to remember that the on-demand economy is not introducing the serpent of casual labour into the garden of full employment: it is exploiting an already casualised workforce in ways that will ameliorate some problems even as they aggravate others.

The on-demand economy is unlikely to be a happy experience for people who value stability more than flexibility: middle-aged professionals with children to educate and mortgages to pay. On the other hand it is likely to benefit people who value flexibility more than security: students who want to supplement their incomes; bohemians who can afford to dip in and out of the labour market; young mothers who want to combine bringing up children with part-time jobs; the semi-retired, whether voluntarily so or not.

Megan Guse, a law graduate, says that the on-demand model allows her to combine a career as a lawyer with her taste for travel. “A lot of my friends that have gone the Big Law route have these stories about having to cancel weddings, vacations and miss family events. I can continue working while being in exotic places.” Flexibility is also valuable for elite workers who want to wind down after decades of selling their soul to their companies. Jody Greenstone Miller, the founder of Business Talent Group, says that her company’s comparative advantage lies in rethinking corporate time: by breaking up work into projects, she can allow people to work for as long as they want.

A limited Utopia

The on-demand economy is good for outsiders and insurgents—and for entrepreneurs trying to create new businesses using such people. Matt Barrie, the founder of Freelancer.com, links the fate of two groups of potential winners: entrepreneurs in the rich world who have few resources will be able to link up with workers in the poor world who have little money. In Europe the labour market drives a wedge between insiders who have lots of protections and outsiders who don’t; on-demand arrangements may give outsiders a chance of breaking in. Thus in countries such as France, Italy and Spain, on-demand companies may improve the job chances of the young unemployed.

If this seems attractive, it is also a measure of the way that the on-demand economy will contribute to pressure to reduce labour rights in all sorts of situations; a growing abundance of on-demand employees with no normally accepted rights such as sick-pay and overtime will give employers at firms with more standard structures an incentive to cut back. The more such pressures spread, the more protests against “Plattform-Kapitalismus” the world is likely to see.

The on-demand economy will inevitably exacerbate the trend towards enforced self-reliance that has been gathering pace since the 1970s. Workers who want to progress will have to keep their formal skills up to date, rather than relying on the firm to train them (or to push them up the ladder regardless). This means accepting challenging assignments or, if they are locked in a more routine job, taking responsibility for educating themselves. They will also have to learn how to drum up new business and make decisions between spending and investment.

At the same time, governments will have to rethink institutions that were designed in an era when contract employers were a rarity. They will have to clean up complicated regulatory systems. They will have to make it easier for individuals to take charge of their pensions and health care, a change which will be more of a problem for America, which ties many benefits to jobs, than Europe, which has a more universal approach. They will also have to encourage schools to produce self-reliant citizens rather than loyal employees.

One of Gilbert and Sullivan’s oddest operettas, “Utopia Limited—or the Flowers of Progress”, focuses on an exotic South Sea island which, under the influence of Victorian industrialism, sets about turning all the inhabitants into limited companies. It is rarely performed today, in part because the targets of its on-the-nose-in-1893 satire seem remote. But perhaps, after a century in which companies were vast things, such a satire of corporate individualism is due for a revival or two. If so, the piece will be easier than ever to stage: if there are not already on-demand services that can provide Polynesian props, semi-retired set designers and down-on-their-luck tenors at the swipe of a screen, there soon will be.